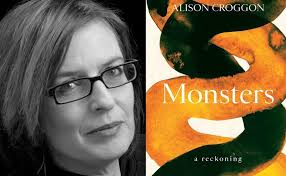

Book Review: Monsters – a reckoning by Alison Croggon

Monsters – a reckoning is a difficult book. Germane to the moment we as Australians find ourselves in, and overdue in national conversation that is, all too often, reductive and obstinately self-exculpatory on the subject of its colonial legacy and present.

Difficult, also, for Croggon personally, who situates herself as a white woman examining herself and her (fraught) family relationships, looking at ‘[a]ll these secrets that everybody knows’, with critical rigor, and who does not fall back on excuses, nor languish in unproductive performative guilt. ‘It’s hard to write this…’ she confesses. ‘I want to take this shame and make it into something else, a tool, a door, a window, a seed, a flowering, a libation, an offering to the wounded earth…’

dentity politics has been roundly attacked – from the Right for its insistence on dismantling narratives of Western cultural supremacy and auxiliary paradigm of heteronormative patriarchy, but also from some parts of the Left, who view it as a Hydra-headed offshoot of neoliberalism; a distraction, holding back real systemic change.

On Breakfast TV™, it’s led to hyperventilation over ‘cancel culture’, and on ‘woke Twitter’, to a torsion of contradictory messages about how to be a white ‘ally’ and act in solidarity with people of colour, without (yet again) seizing platforms and recentering whiteness – and white people – as default protagonists.

Croggon writes: ‘I can only write my own story, but how is this not the same story that has been told, over and over again, at the expense of so many other stories? How is this not the story of the conquerors?’ This is the paradox that Croggon confronts, and here she is witty, self-reflective, raw. ‘The pathology of whiteness is that it can’t face itself’, she asserts, and then admits: ‘I carry the mantle of whiteness into all my dealings, large and small, unconsciously… I speak, write, think Englishness.’ She describes reading Edward Said’s Orientalism, which, she recalls made her ‘more and more ashamed as I realised that the mirror he was holding up reflected my own face. It was the first time I consciously recognised how empire shaped my life.’

Monsters is difficult thrice over as Croggon’s discomfiture extends into the book’s restive genre categorisation, described as a ‘hybrid of memoir and essay’. Part of the work focuses on an unresolved feud with her younger sister, woven within a context of intergenerational dysfunction and trauma. Croggon ponders whether her sister ‘needs’ to create a monster figure out of her: ‘Sometimes, in nauseating moments of vertigo, I wonder if the things she claims about me might somehow be true.’ She renders their vicious fights, one memorably involving a locked bathroom door and a heavy pepper grinder, and what she names ‘our ridiculous version of the oppression Olympics. I always despised myself after those arguments.’

Croggon’s background as a poet is tangible. She dissects etymology and her breadth of research is sprinkled with reference to Jean Genet, Wallace Stevens, Arthur Rimbaud, Audre Lorde, and Sylvia Plath. (‘I read hungrily, messily, without discipline, as I still do.’) Her language is flavoursome: ‘I have often thought writing to be a cold act, a hammer on hot iron. In order to write at all, I must split my self into she who feels and she who writes… But I persist, nevertheless, in believing that writing can also be an attempt at freedom, a struggle to recognise and break confining patterns.’

In her persistence, she drags out unpleasantness, stashed as skeletons in so many colonial family closets. ‘My forebears, all of them, were loyal servants of the British Empire, one of the biggest machineries of violence that has ever existed.’ She uses the now-common neologism ‘gaslighting’ to describe the stories generations of white children have grown up on to normalise attitudes of racial hierarchy: ‘Nothing is innocent, not even Peter Rabbit.’

Monsters is decidedly not a ‘book club’ book, for that all-too-true cliché of white women drinking white wine, but it should be. ‘The British, I was told all my young life, ‘helped the natives’,’ writes Croggon. ‘We came to these dark countries out of the goodness of our hearts to bring the Light of Civilisation.’ I was told something similarly revolting almost verbatim by my grandparents as a white child in the late 1980s.

The inextricability of gender from race is something that Croggon necessarily strives to unpack: ‘Patriarchy… still remains curiously invisible. Among its most grievous harms is how it distorts and destroys relationships between women… Is it surprising that western women despise each other, and, underneath, ourselves?’